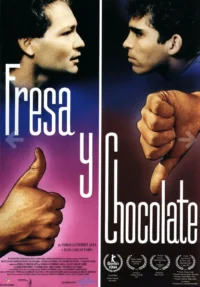

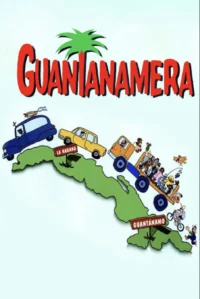

The analysis of Adorables mentiras focuses on the articulation between gender, language, and the cinematic device as fundamental axes for understanding the social, symbolic, and affective dynamics that permeate Cuba in the late 1980s. Through ordinary characters and seemingly banal situations, the film reveals how double moral standards, structural machismo, the hierarchization of desire, and material precariousness become naturalized in everyday life, while cinema and language function as privileged spaces of simulation, displacement, and veiled critique. Without formulating an explicit thesis or offering solutions, the film constructs a narrative in which lying operates as a mechanism of adaptation and survival, exposing the tensions between official discourse, lived experience, and social imaginaries at a moment of historical transition.

Analysis of Adorables mentiras (synthetic reading)

Summary of gender-related elements

The gender analysis of Adorables mentiras highlights structural machismo as an organizing principle of affective, symbolic, and social relationships in late-1980s Cuba. The film does not present machismo as an individual deviation, but as a shared and naturalized norm, reproduced through everyday language, subtle gestures, and the moral hierarchies that govern both private and public life. Socially legitimized masculinity—embodied by Jorge Luis—rests on symbolic impunity, sexual double standards, and the instrumentalization of art as an alibi for emotional and domestic neglect, while fidelity and sacrifice are imposed as structural demands on women.

Within this framework, the female characters articulate differentiated modes of inscription within the patriarchal order: Isabel as a figure of adaptation and negotiation of the body as symbolic capital; Flora as the material provider and active reproducer of the norm; and Nancy as an excessive, marginalized body, punished for failing to channel her sexuality toward power. The film reveals how machismo, homophobia, and racism operate interdependently, hierarchizing bodies and desires, and demonstrating that gender-based violence—physical, symbolic, and discursive—is not an exception but a structural condition of this social order.

Summary of discourse analysis elements

From a discursive and cinematic perspective, Adorables mentiras employs film language as a critical device that exposes the gap between public discourse and lived experience. Cinema emerges as a space of simulation, prestige, and hierarchy, where symbolic capital replaces real value and imposture becomes a survival strategy within the cultural field. Through its metacinematic structure, the film reveals how lived experience—especially women’s experience—is extracted, manipulated, and transformed into “narrative material,” stripped of its ethical dimension.

Mise-en-scène, the use of objects, narrative ellipses, and editing reinforce this critique without the need for explicit emphasis. Repetition, rather than transformation, structures the film’s conclusion: power does not collapse; it readjusts. The cinematic device thus constructs a bitter satire in which the exposure of lies does not lead to sanction, but to their functional integration within the system, consolidating double standards as a stable form of social equilibrium.

Summary of sociolinguistic analysis elements

From a sociolinguistic perspective, the film conceives language as an ideological archive that not only reflects social reality but actively produces it. The different registers—bureaucratic, moralizing, colloquial, intimate, and marginal—configure a hierarchical map in which speech legitimizes or excludes. Official discourse, embodied in administrative and technocratic language, operates performatively: it does not communicate but rather confirms belonging and reproduces power, systematically distancing itself from everyday experience.

By contrast, colloquial and marginal registers condense values, prejudices, and naturalized forms of violence that circulate as common sense. Seemingly banal expressions convey racism, machismo, and sexual stigmatization, while the gaze toward the foreigner introduces an external instance of moral and social validation. The film thus constructs a model of indirect enunciation, in which critique is not articulated frontally but displaced into side comments, rumor, and irony, reproducing a discursive practice widely recognizable in Cuba at the time: saying without saying, denouncing without direct confrontation.

Below is the detailed analysis of the film. This approach allows us to trace how the various thematic and discursive axes that structure the work unfold progressively, attending both to narrative shifts and to the transformations that emerge across the film as a whole.