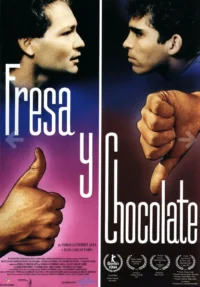

Cuban Superstitions

In this article, we explore a topic deeply rooted in everyday Cuban life: superstitions. Since colonial times, Cuban culture has been steeped in popular beliefs that, although often considered superstitions, remain a fundamental part of daily and family interactions. These beliefs, passed down from generation to generation, have survived over time and continue to shape the Cuban worldview today.

The video we analyze reflects several of these beliefs, many of which are related to luck, fate, and omens. The protagonist mentions well-known superstitions, such as the bad omen of opening an umbrella indoors or the curious positive omen of stepping on dog excrement. In Cuba, these everyday actions are often interpreted as signs of fate, influencing people’s behavior, as they try to avoid bad luck or attract good fortune through small rituals.

This video also offers a glimpse into how language reflects these beliefs. Expressions like “solavaya” (used to ward off bad luck) or the act of knocking on wood are examples of how deeply rooted superstitions are in Cuban culture.

The relaxed and colloquial tone with which these beliefs are discussed shows that they are not just superstitions, but also an integral part of humor and family relationships, creating a bridge between the past and the present, where popular knowledge remains alive.

Let’s Watch the Cuban Superstitions video!

Transcript of the Video

1. Cultural Context

The video touches on several common superstitions in Cuba, which are deeply woven into daily life and popular beliefs passed down through generations. These superstitions are rooted in Cuban culture and are the result of a rich blend of cultural influences dating back to colonial times. In particular, two significant cultural sources have profoundly shaped these beliefs: African influence and Christianity brought by the Spanish colonizers. These two traditions not only coexisted but also fused, creating a unique cultural syncretism in Cuban society.

The African influence in Cuban superstitions primarily comes from the enslaved people brought to the Island during the colonial period. These groups carried their spiritual beliefs and practices, often deeply connected to ancestral spirits and the interpretation of natural signs. Many superstitions related to luck and omens, such as the belief that stepping in dog poop brings good fortune, have roots in these African traditions, where signs from the environment were seen as spiritual messages.

The African legacy in Cuban culture is so profound that it is reflected in popular expressions like “El que no tiene de congo tiene de carabalí.” This phrase refers to two ethnic groups brought to the Island during colonial times, the Congos and the Carabalí, and is used to highlight that, regardless of one’s background, everyone carries a mix of African influences in their heritage. It emphasizes the shared African ancestry and underscores how ethnic diversity has shaped Cuban identity. The expression highlights how cultural diversity has enriched Cuban identity, making these roots an essential part of daily life and the way Cubans understand and interpret the world.

On the other hand, religious syncretism has played a crucial role in shaping these beliefs. The fusion of Christianity with African religions gave rise to a unique cultural phenomenon known as Santería, where Catholic saints were blended with African deities, or orishas. This syncretism not only merged Spanish and African religious practices but also permeated popular beliefs and everyday superstitions. For instance, the act of knocking on wood, though of European origin, has been incorporated into Cuban culture, aligning with spiritual protection practices. In this way, Christian and African traditions are intertwined in a single everyday gesture.

2. Superstitions in the Video

In many cultures, it is common to encounter popular superstitions like avoiding a black cat crossing your path or crossing your fingers to bring good luck. However, in Cuba, these beliefs are much more specific and deeply rooted in the Island’s cultural context.

The video explores some of the most unique superstitions in Cuban life, highlighting how beliefs about luck, destiny, and protection from the unknown manifest in distinct ways in people’s daily lives. These practices reflect the cultural blend that characterizes Cuba, where African, Spanish, and local influences come together in a syncretism rich with rituals, symbols, and unique meanings.

Not Opening Umbrellas Indoors

This superstition, present in various cultures, has a particular significance in Cuba. It is believed that opening an umbrella inside the home attracts bad luck and unexpected problems. In the video, the mother insists that an umbrella should not be opened under a roof because they already have enough “arrastre,” a term referring to the emotional burdens and difficulties they face in their daily lives. This highlights the need to avoid adding more weight to their everyday struggles.

The origins of this belief may trace back to colonial times, when umbrellas were considered a luxury item. Opening one in an enclosed space might have been seen as an inappropriate or out-of-place gesture, potentially inviting negative energy. While it is difficult to pinpoint a definitive origin, this idea has evolved over time.

In Cuban culture, where popular beliefs are deeply tied to spirituality and energies, opening an umbrella indoors could symbolize exposing oneself to negative influences.

Stepping in Dog Poop

In many places, stepping in dog poop is associated with something unpleasant and negative. However, in Cuba, this action has an entirely opposite connotation: it is believed to bring good luck. This cultural contrast is fascinating, demonstrating how the same act can have radically different meanings depending on the context. In Cuban superstition, stepping in dog poop is a sign that prosperous times or unexpected opportunities are on the horizon.

This belief may have roots in African culture, where certain acts or encounters with animals and nature were seen as messages from spirits or gods. However, it is also a belief in Spain, which may have brought the superstition to Cuba or vice versa. In Cuban culture, this view has persisted and intertwined with urban life, where dogs are constant companions in the streets. Through this lens, what might be considered an annoyance in other cultures becomes a symbol of hope and prosperity in Cuba. The grandmother’s affirmation that “good things are coming” reflects how this superstition serves as a reminder that even the most unpleasant situations can bring about something positive.

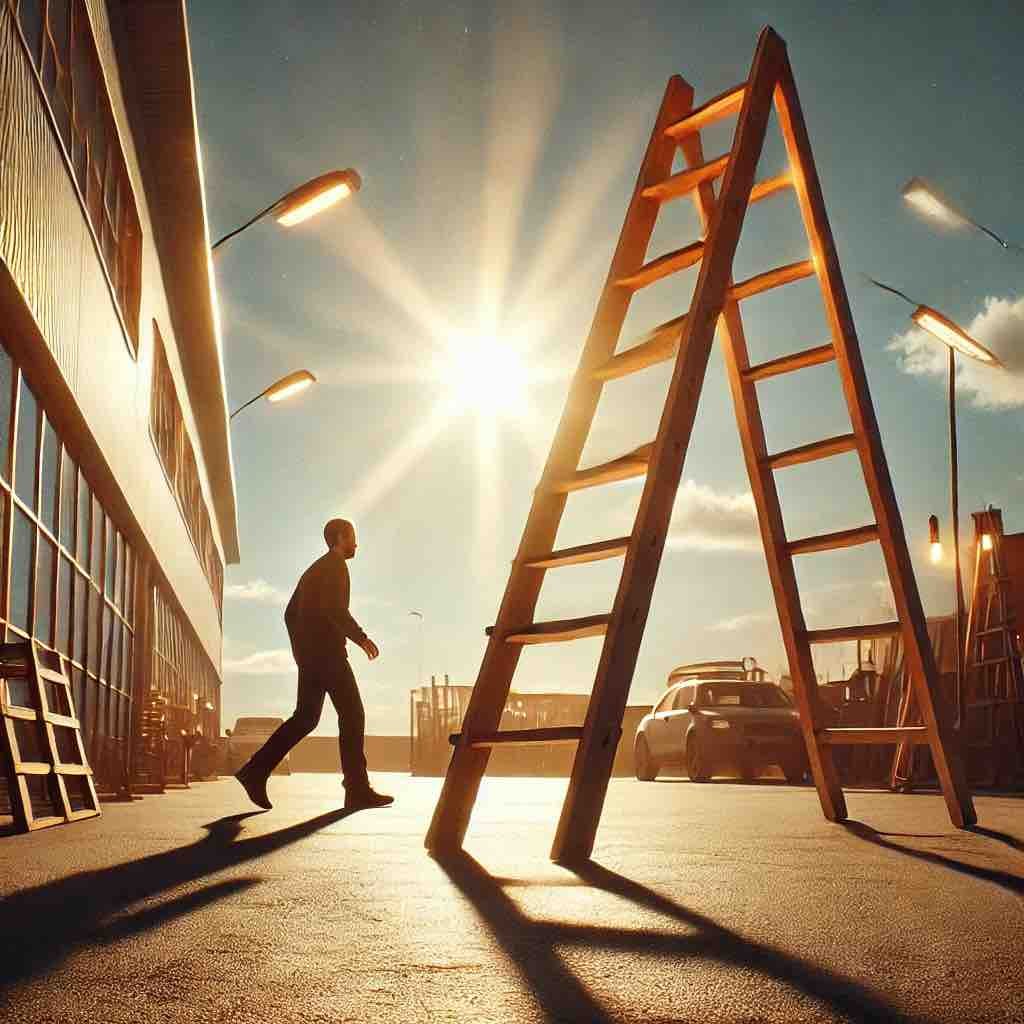

Avoiding Walking Under Signs or Ladders

This idea is common in many cultures and is deeply rooted in Cuban superstition. It is believed that walking under a sign or ladder can “ruin plans,” meaning it could obstruct a person’s projects or desires.

In the video, the mother mentions that this could affect her plans to travel, reflecting a popular belief that certain actions are perceived as obstacles to progress or impediments to achieving goals. It’s worth noting that when Cubans talk about “plans,” they often refer to traveling as one of their top priorities.

This superstition likely stems from both European beliefs brought by colonizers and African traditions, integrated through Cuba’s religious syncretism. The idea that walking under a structure could alter one’s destiny is deeply embedded in Cuban religious syncretism, where African and European beliefs blend to form concepts of bad energy and bad omens.

For many Cubans, plans are often subject to forces beyond their control, so following these beliefs may be a way to feel some sense of control over the future.

Itchy Hands

This superstition is related to money and personal finances. In Cuba, as in many other cultures, it is said that if your right hand itches, you will receive money or come across unexpected income, while if your left hand itches, you will face a significant expense. In the video, this belief is mentioned humorously, but many people take it seriously.

Additionally, in a context where economic difficulties are a daily reality for many, these small superstitions offer a sense of control or foresight over what the future might bring. The phrase “you will get money” is common in informal conversations, showing how this way of thinking remains alive in modern Cuban mentality.

Knocking on Wood

The expression “knocking on wood” is a superstition widespread across various cultures, including Cuba, and is related to protecting oneself from bad luck or negative energies. In the video, the mother mentions this practice after discussing potential misfortunes, highlighting how this custom is part of everyday life on the Island. The idea behind knocking on wood is to invoke a kind of protection or to ward off negativity that has been mentioned, hoping that it doesn’t come true.

Its origin is uncertain, but it’s believed to come from ancient pagan beliefs, where trees, considered sacred, were thought to house spirits that offered protection. By knocking on wood, people sought to invoke the help of these spirits, or at least avoid attracting the attention of evil forces. In Cuba, this practice has remained in use, and knocking on wood is frequently used in situations where people want to avoid a bad omen or counteract a negative statement. Wood, as a natural element, continues to be seen as a symbol of protection against adversity, and its use in Cuban superstitions reinforces the connection between people and protective energies in daily life.

Hitting Your Elbow

In Cuba, hitting your elbow is humorously linked to the mother-in-law, reflecting how many superstitions are intertwined with family relationships. The popular belief suggests that if you bump your elbow, your mother-in-law is either speaking badly of you or thinking about you. While this superstition is usually taken in a lighthearted way, it plays on the stereotype of mothers-in-law as critical or difficult figures in families.

Beneath the surface, this “elbow bump” highlights the significance of family dynamics in Cuban culture, where close relationships—like the one with a mother-in-law—are central. In many Cuban households, mothers-in-law often live closely with their sons- or daughters-in-law, which can lead to intense coexistence. This type of belief serves to lighten tensions and bring humor to daily family interactions.

On a broader level, this superstition reflects how Cubans, like many other cultures, use humor as a way to cope with everyday challenges.

A Rocking Chair Should Not Rock on Its Own

The superstition that a rocking chair should not move on its own is deeply rooted in Cuban beliefs about spirits or the souls of the dead interacting with the living world. According to this tradition, when a rocking chair rocks with no one in it, it can signal the presence of a spirit.

This seemingly harmless act of letting a chair rock by itself can be interpreted as an invitation for the dead to draw near, something that is often seen as unsettling or even dangerous.

In the Cuban context, the syncretism between Afro-Caribbean religions, like Santería, and popular beliefs places spirits at the center of everyday life. The idea that ancestors’ spirits can manifest or be present in physical spaces is common.

Allowing a rocking chair to move unoccupied could symbolize a disrespectful act toward the dead, potentially bringing bad luck or problems to those who fail to heed these signals from the afterlife. This superstition embodies a mix of veneration and fear toward the supernatural, reflecting Cuba’s rich spiritual and cultural heritage.

These beliefs demonstrate how spirituality and superstitions play a crucial role in daily life, influencing behaviors and attitudes towards the inexplicable.

– Wearing an Azabache Stone: The use of azabache as a protective amulet in Cuba traces back to African and Spanish beliefs, where it was thought to absorb negative energies. Its use, especially for protecting children, is based on the idea that it can deflect the evil eye and keep those who wear it safe.

– Don’t Sweep Towards the Door: Sweeping the house in the direction of the main door is believed to drive away good luck and send away visitors.

3. Language and Vocabulary

In the analysis of the language and vocabulary of the video, some essential aspects can be highlighted that showcase the richness and peculiarity of Cuban Spanish.

Expressions to Ward Off Bad Luck

The word “solavaya“ is heard, an expression used to ward off bad luck or to wish that something bad does not happen. This term is part of Cuban folklore, and although it is mainly used in superstitious contexts, it reflects how humor is mixed with everyday popular beliefs in Cuban culture.

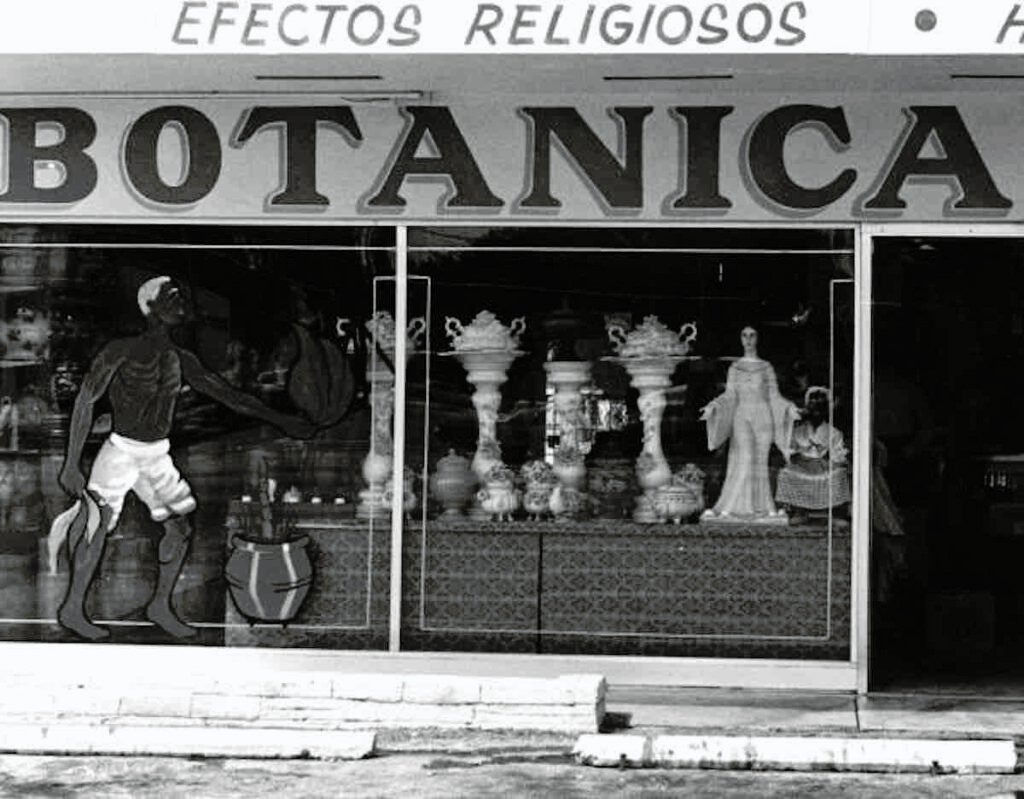

– You have to go to Guanabacoa: This is a popular phrase in Cuba used when someone has bad luck or is going through a negative streak. Guanabacoa is a municipality in Havana known for its deep connection to santería and other Afro-Cuban religious practices.

Saying that someone must “go to Guanabacoa” implies that this person needs a spiritual cleansing or to perform some ritual to change their fortune.

References to Herbs and Traditional Remedies

The herbs “espantamuerto“ and “rompesaragüey“ mentioned in the video are plants with strong symbolism in santería and healing practices in Cuba. These herbs are believed to have the ability to cleanse bad energies and offer protection from negative influences. The use of these terms highlights how spiritual beliefs are integrated into everyday speech.

In Cuba, the use of herbs and traditional remedies has been a deeply rooted practice in daily life, passed down from generation to generation. These herbs, known for their medicinal and spiritual properties, are used both to treat physical ailments and to cleanse bad energies or improve luck. Among the most commonly used are rompesaragüey, espantamuerto, basil, vencebatalla, and palo vencedor, each with a specific purpose in the spiritual and healing realm.

The use of these plants reflects not only the natural richness of the Island but also the mixture of cultures, primarily African, which has left an indelible mark on Cuban popular beliefs.

The yerbero (herbalist), the name given in Cuba to the person responsible for collecting and selling these herbs, has been a key figure in both rural and urban communities. These individuals possess deep knowledge about the plants, their uses, and combinations, and often act as spiritual guides.

With the exodus of Cubans to Miami and other U.S. cities, these practices crossed the sea and transformed into popular Botánicas, specialized shops selling herbs, candles, and religious items. Botánicas have become a cultural reference point for Cubans seeking to connect with their roots and continue the rituals that are so common in their country of origin.

The custom of using herbs to improve luck or ward off bad vibes is deeply tied to beliefs of African origin that arrived in Cuba with enslaved people and merged with indigenous and Spanish traditions. This practice is so common that even in the 21st century, many people still believe in the power of a good herbal bath to ward off bad luck. Herbs such as rue, rosemary, and rompesaragüey are used in both santería rituals and simple home practices, demonstrating how spirituality and nature intertwine in Cuban daily life.

Compound Words

Spanish, particularly its Cuban variant, stands out for its creative capacity to form new words by combining existing terms, reflecting the cultural richness and linguistic diversity of the Island. Compound words like “solavaya,” “rompesaragüey,” and “espantamuertos“ are not just linguistic expressions but also bridges between the everyday and the spiritual. For instance, “solavaya“ is constructed from “sola (alone)” and “vaya (she goes),” transforming into an exclamation laden with meaning that seeks to ward off bad luck. This type of linguistic creation is a clear reflection of the creativity and adaptability of the Cuban people, who find in language a way to express their reality and beliefs.

Through these compound words, the interconnection between language and culture is revealed, where each term encapsulates a set of values and beliefs. “Rompesaragüey,” which combines the verb “romper“ (to break) with “saragüey,” symbolizes the idea of freeing oneself from bad influences, evoking the struggle against the negative in an environment that often faces challenges. Similarly, “espantamuertos“ (to scare or to frighten + dead people) reflects the desire to protect oneself from the unknown and the invisible forces that may disturb daily life. The beauty of these words lies in their ability to condense deep and complex meanings into simple structures, highlighting the rich cultural tradition that gives life to Cuban Spanish and its capacity to transform reality through language.

Use of Diminutives and Affectionate Terms: “mija, mima, mijita”

Throughout the video, there are examples of diminutives such as “mija” (my daughter) and “mima,” which are very common in Cuban Spanish and are used to express affection or closeness. These words, although they literally mean “my daughter” and “my mom,” are used much more broadly in everyday Cuban speech, not only to refer to direct family members but also to address friends, acquaintances, and even strangers in a trusting context.

For example, a friend might greet another with “¿Cómo estás, mija?” to denote closeness, even if there is no family tie. Similarly, a salesperson in a store might refer to a female customer as “mima” while offering help, creating an atmosphere of kindness and familiarity. This usage reflects the warmth and familiarity of everyday interactions in Cuba, where diminutives are not only a sign of affection but also a reflection of the close-knit nature of social relationships. “Mija” and “mima” add an emotional layer to the language and are indicators of familial and affectionate relationships within Cuban culture, emphasizing how language conveys not just information but also feelings and personal connections.

The term “mijita” is a more affectionate and diminutive variant of “mija,” used in Cuban Spanish to refer endearingly to a young woman or girl. It is often employed in a family or friendly context but is also used among acquaintances and in informal situations to establish a warm and friendly tone. For instance, a mother might call her daughter “mijita” when speaking tenderly to her, or a friend might address another in this way to express camaraderie. This word reflects the rich tradition of using diminutives in Cuban culture, where language becomes a vehicle for conveying affection and warmth.

In the video, we also see that the mother uses the term “hermana” (sister) to refer to her daughter, which reflects a colloquial and affectionate way of addressing someone on the Island. This expression, while suggesting closeness, is often used in contexts of reprimand or to get someone’s attention. The use of “hermana” in a demanding tone intensifies the familiarity of the exchange, highlighting both the emotional bond and the corrective purpose of the conversation.

It is important to note that the intonation of these expressions plays a key role in their meaning, as it can convey different nuances. Depending on how it is pronounced, “mijita” can express a more maternal and tender tone, a gentle reprimand, or even a friendly call for attention. This highlights how, in Cuban culture, oral language communicates not only ideas but also emotions and levels of closeness, reinforcing the warm and affectionate nature of social interaction on the Island.

Having a Burden

In Cuba, when speaking of “arrastre“ (dragging), it refers to a load of bad luck or accumulated problems that accompany a person. This term suggests that someone is dragging a series of difficulties or unfortunate situations, generating a sense of pessimism or exhaustion. In the context of the video, the mention of “arrastre” reflects the perception that, amidst daily challenges, it is necessary to avoid any action that might attract even more bad energies. The concept of “arrastre” is related to the idea that negative energies or negativity are not only experienced individually but also carried over from one event to another, creating a cycle of misfortunes or difficulties.

This term may have links to African influences and religious practices in Cuban culture, where it is believed that negative energies, bad vibes, or even evil spirits can become “stuck” to a person, leading them to have recurring problems in various aspects of their life, such as work, relationships, or health.

The expression “ya tenemos bastante arrastre” (we already have enough drag) in the context of a casual conversation in Cuba reflects the perception that there is already enough bad luck or negative burden in life, and one does not wish to add more problems. In the case of the video we’re analyzing, the reference to not opening an umbrella indoors relates to avoiding increasing that “arrastre,” preventing the attraction of more bad luck or difficulties.

The Rocking Chair

In standard Spanish, the term “sillón“ (armchair or rocking chair, depending on the region) refers to an individual seat with arms and a backrest, generally cushioned and more comfortable than a simple chair. It is a word widely used across the Spanish-speaking world to designate this type of furniture that offers a higher level of comfort.

However, in the Caribbean, and particularly in Cuba, the term “sillón“ acquires a more specific meaning. In this region, a “sillón“ is not simply a seat, but a piece of furniture with rockers that is used for rocking. These rocking chairs are often made of wood and wicker, materials more suitable for the tropical climate, and have become an emblematic element of Cuban and Caribbean homes.

The rocking chair symbolizes the Caribbean lifestyle, where the heat and tranquility invite moments of rest in open spaces, such as the porches and patios of houses. Historically, the rocking chair was compared to a “comadrita” (a close friend or companion) for its role in daily life, as it was often the preferred furniture for family conversations, neighborly visits, and the rest of the elderly.

This type of chair has become part of the traditional furniture in many regions of the Caribbean and Central America, becoming a representative piece not only for its functional design but also for its symbolic value in the culture of outdoor relaxation. The custom of rocking in a chair is part of the Caribbean lifestyle, which privileges the leisurely enjoyment of time and social relationships.

4. Cultural Implications

Superstitions in Cuba are cultural mechanisms that help people manage the uncertainty and challenges of daily life. In a context where economic and social difficulties are common, these beliefs offer a form of symbolic control. Humans have an inherent need to believe in something supernatural, and despite the fact that, after 1959, Cuba became a forcibly atheist country, the population continued to cling to their beliefs, demonstrating a notable duality: even in an environment that rejects the spiritual, traditions remain alive. This duality reveals how, even in an environment that rejects the spiritual, people find ways to keep their traditions alive.

Over time, the reacceptance of religion has led to a notable increase in the practice of beliefs that resurge after prohibitions, reflecting the desire of Cubans to reconnect with their spiritual roots. Through rituals such as knocking on wood or avoiding walking under a ladder, Cubans attempt to prevent bad luck and attract well-being, reflecting their desire to dream of a better world. The video addresses these themes with humor, emphasizing that, for many, these superstitions are an integral part of their daily lives. They reflect the ability of Cubans to dream of a better world despite adversities.

Popular beliefs function not only as a means of protection but also as a way to resist adversity with humor and hope. The subtext reveals a deeper need: the quest for security in an uncertain environment. Superstitions, fueled by centuries of African and Christian influence, provide Cubans with a sense of control and connection to their cultural heritage. This becomes a fundamental part of their identity, allowing them to dream of a better future while facing the complexities of their reality.

The cultural implications of superstitions in Cuba are diverse and profound, reflecting not only individual beliefs but also social, historical, and psychological dynamics. It would be good to consider some additional points regarding the cultural implications of these beliefs:

These superstitions are not only a reflection of the rich cultural heritage of Cuba but also act as vital tools that help Cubans navigate the complexities of their daily lives.

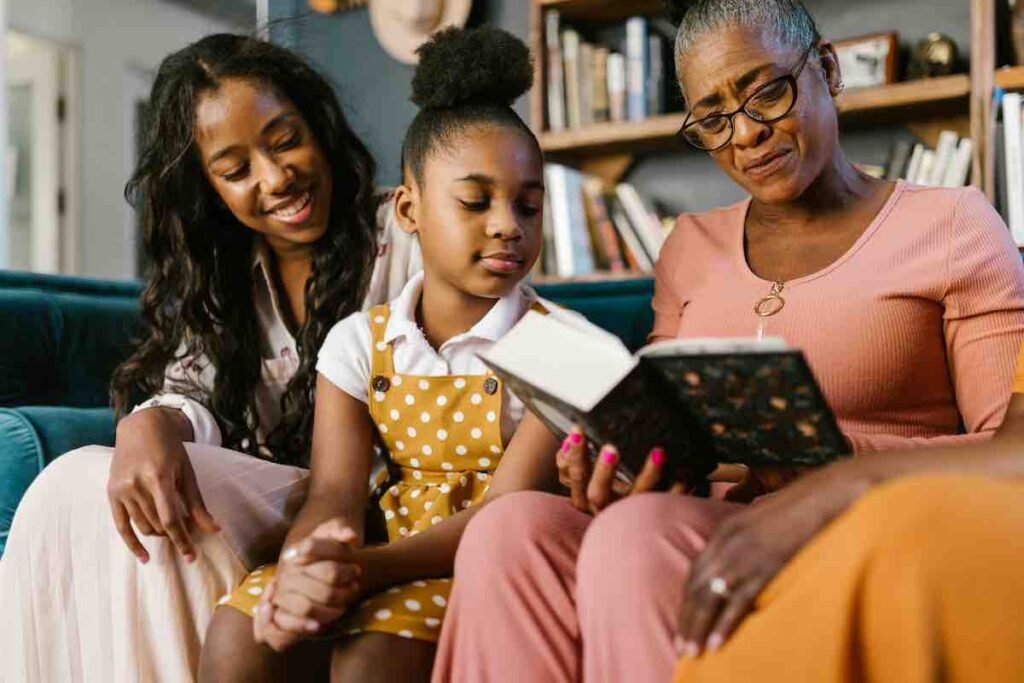

5. Character Analysis

Superstitions on the Island, as in many other cultures, are passed down from generation to generation, and this family legacy is visible in the video. Mothers and grandmothers act as bearers of ancestral knowledge, which includes rituals, warnings, and beliefs about luck and fate. It is observed how the mother and grandmother share this knowledge with the daughter, who, despite appearing more skeptical, cannot help but be influenced by them.

This dynamic reflects how ideas about luck and protection against the unknown are transmitted naturally in family conversations, reinforcing a divine fabric that traces back to ancestors.

Grandmothers, as wise figures, preserve these traditions and perpetuate them, ensuring that the young remain connected to the beliefs that their own forebears practiced. Although they may appear less convinced, as happens in the video, the weight of family tradition is strong. In many cases, the repetition of these rituals and coexistence with these ideas ultimately permeates the new generations, who may internalize the superstitions without fully questioning them.

This cultural heritage goes beyond the superstitious; it is a way to preserve family and cultural identity. The beliefs transmitted from mothers to daughters protect against negative energies and keep alive a bond with the ancestors who arrived on the Island under difficult circumstances, carrying with them their religions, fears, and hopes.

In this sense, Spanish colonization, although it attempted to impose a different culture, could not combat the weight of the African identity that became rooted on the Island. Spanish culture, with its own beliefs and practices, was enriched and transformed by African influence, leading to a process of syncretism in which the traditions and rituals of both cultures coexisted and merged.

African religions brought a profound sense of community and spiritual connection, contrasting with the individualistic view of Spanish Catholicism. This syncretism allowed elements such as santería and popular beliefs to be integrated into the daily lives of Cubans, creating a vibrant and resilient culture that preserves the essence of these traditions.

In this way, superstitions not only act as a way to cope with uncertainty but also as a legacy that connects current generations with their deepest roots, ensuring that ancestral wisdom remains alive in contemporary Cuba. The rich mix of cultural influences has allowed African beliefs and practices to endure, despite attempts at assimilation and control, and to continue being an integral part of Cuban identity today.

This intergenerational relationship is fundamental to the construction of cultural identity, where every superstition, every ritual, and every conviction is part of a cultural mosaic that reflects the history, struggles, and resilience of the Cuban people. Its persistence in daily life demonstrates that, despite adversities and prohibitions, the essence of culture and traditions is never entirely lost.

6. Relevance for Spanish Students

The relevance of this video for Spanish students goes beyond simply learning vocabulary. By observing how Cuban superstitions are intertwined with daily life and language, students can gain a richer insight into the Spanish spoken on the Island. These popular beliefs not only reflect the cultural context of Cuba but also reveal how generations pass on their traditions and values through language. At the same time, it allows them to refine their linguistic skills and delve into a crucial aspect of Cuban culture.

Furthermore, the study of superstitions provides an excellent platform to explore how culture influences the structure of the language. By understanding the expressions and meanings behind phrases like “solavaya” or “tocar madera,” students can see how the beliefs and values of a people are reflected in their way of speaking. This analysis offers an opportunity to reflect on the richness of Cuban Spanish and how certain linguistic aspects are deeply rooted in local identity and customs.

Finally, by delving into topics like superstitions and their origins, students not only learn a language but also immerse themselves in how Cubans interpret the world around them. The mix of African, Spanish, and Creole heritages creates a unique space where language and popular beliefs intertwine, allowing for an understanding of how the past continues to influence modern life.

If you wish to explore how Cubans carried their rich baggage of traditions when leaving the Island and how these adapted to their new environment, or how the Spanish cultural heritage remains present in our country, I recommend exploring the following materials:

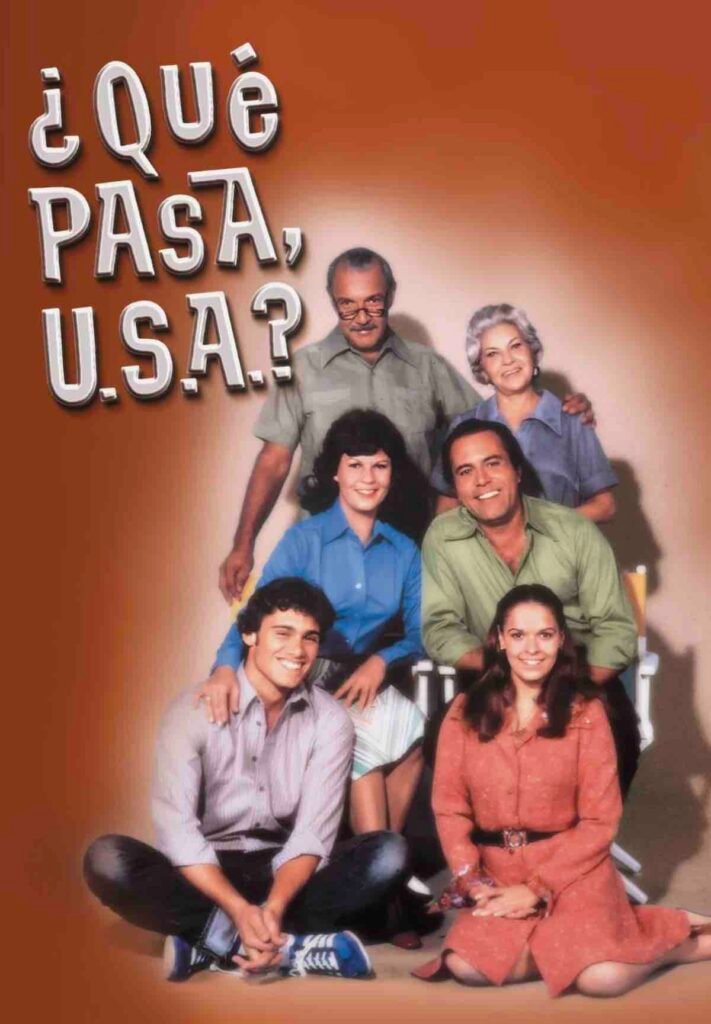

Series: What’s Happening USA?, Episode “Santería vs Catolicismo”

In the series ¿Qué pasa USA?, the experience of Cuban emigrants in Miami is addressed in a humorous and reflective way, exploring their efforts to adapt to a new environment without losing their cultural identity. In one of the episodes titled “Santería,” the influence of the African religion and the syncretism that has characterized Cuban spirituality is examined.

Through endearing characters, the series illustrates how beliefs in Santería intertwine with the new daily life of Cubans, showing both the continuity of these traditions in exile and the need to maintain a connection to their roots.

This approach not only offers a humorous look at superstitions and rituals but also highlights the cultural resilience of the Cuban community in a context where they face social and economic challenges, reaffirming the importance of the African heritage in their identity.

Book: Dreaming in Cuban by Cristina García

If you want to explore more about how Cubans have carried and adapted their traditions when emigrating, I recommend the book “Dreaming in Cuban” by Cristina García.

This novel offers a profound reflection on Cuban identity and the experience of the diaspora, exploring the complex family relationships and the impact of history on the lives of its characters. The work highlights how religion and customs transform in the new environment, echoing the experiences of those who have left the Island in search of new opportunities.

Song Toca Madera by Joan Manuel Serrat

Superstitions carry significant weight in the original Spanish culture, of which Cuban culture is a heir. This connection manifests in a series of popular beliefs that seek to attract good luck and ward off negative energies.

Elements like “tocar madera,” “avoiding passing under a ladder,” or making the gesture of “spitting backward” are common practices in Spain that have also found resonance in Cuban culture.

The Spanish influence is reflected in the richness of Cuban superstitions, which often combine African and Spanish traditions. A notable example of this heritage is the song “Toca madera” by Joan Manuel Serrat, which encapsulates this need to perform symbolic rituals in daily life.

I invite you to listen to this song to notice how, both in Spain and Cuba, superstitions are an essential part of cultural identity. Additionally, I encourage you to reflect on the true origin of these beliefs and question their geographical flow. Do they come from Spain? From Africa?

We encourage you to share in the comments any other superstitions you know or have heard in your environment. It will be interesting to discover how these beliefs vary from one place to another!