Cuban Typical Food

I have noticed that on social media, there are a large number of videos where Cubans share their daily lives, customs, and worldview. However, there are few spaces dedicated to explaining in depth the meaning of what they say or how their words reflect Cuban traditions and culture. For those studying Spanish and looking to understand the context behind these conversations, there is a vast world to discover.

That’s why I am starting a series in which I will analyze this type of videos, examining the language and its expressions, everyday expressions, and cultural aspects. My goal is to offer a deeper perspective that not only helps to understand what is being said, but also why it is said in that particular way. Join me on this journey through Cuban Spanish!

The first video I will analyze, titled This is what I eat in a day living in Cuba, is an excellent example that not only highlights Cuban typical food, but also how language reflects the country’s cultural and social reality. Throughout this brief 1-minute and 30-second narration, the speaker describes her daily eating routine, using colloquial expressions, regional variations, and a fast-paced speech.

This analysis will address the use of Cuban slang, the frequency of fillers like “caballero,” the impact of scarcity, and common phrases such as “se fue la luz” (the power went out), all connected with the context of Cuban traditions and culture.

Let’s watch the video: This is what I eat in a day living in Cuba

Video Transcript

1. Use of Cuban Spanish Variant (Slang)

The video is full of Cuban colloquial expressions that reflect daily life and the idiosyncrasies of Cuba. Some noteworthy examples are:

“Tin”: In Cuba, this word means “a little.” The speaker says “un tin de miel” when referring to the small amount of honey she uses to sweeten the coffee, instead of sugar, which is scarce.

“Recuelo”: Although it is not a standard Spanish word, in the Cuban context, it means reusing the coffee from the previous day, something very common in daily Cuban life due to scarcity. This term reflects the linguistic creativity of the Cuban variant of Spanish.

“Pedacitico“: This is another diminutive used in the video to describe something very small; it is a diminutive of pedazo (portion). The speaker mentions a “pedacitico de huevo,” which reflects a tiny portion. This use of diminutives is typical in Cuban Spanish and shows how colloquial language adds emotional or descriptive nuances.

These expressions give students an approach to a more authentic and realistic Spanish, just as they would hear on the streets of Havana or any other Cuban city. The use of slang helps not only with fluency but also with cultural connection.

2. Diminutives in Cuban Spanish

Diminutives are a common feature of Spanish, but in Cuba and other regions of Latin America, they are often used more frequently to emphasize smallness or add emotional weight. One of the most interesting diminutives is “chirriquitico“, which is an exaggerated form of “chiquitico“, used to refer to something extremely small.

Cultural Use

Diminutives in Spanish serve not only to indicate size but also to convey emotional weight and affection. In many regions, expressions like ‘chiquitico‘ and ‘chirriquitico‘ are commonly used in everyday speech to highlight something small or seemingly insignificant, often with a loving or playful tone. The term ‘chirriquitico,’ in particular, adds an element of exaggeration, frequently infused with humor or charm. Such expressions enrich colloquial speech in various countries, showcasing the diversity of the Spanish language and how diminutives can vary in form and function across different cultural contexts.”

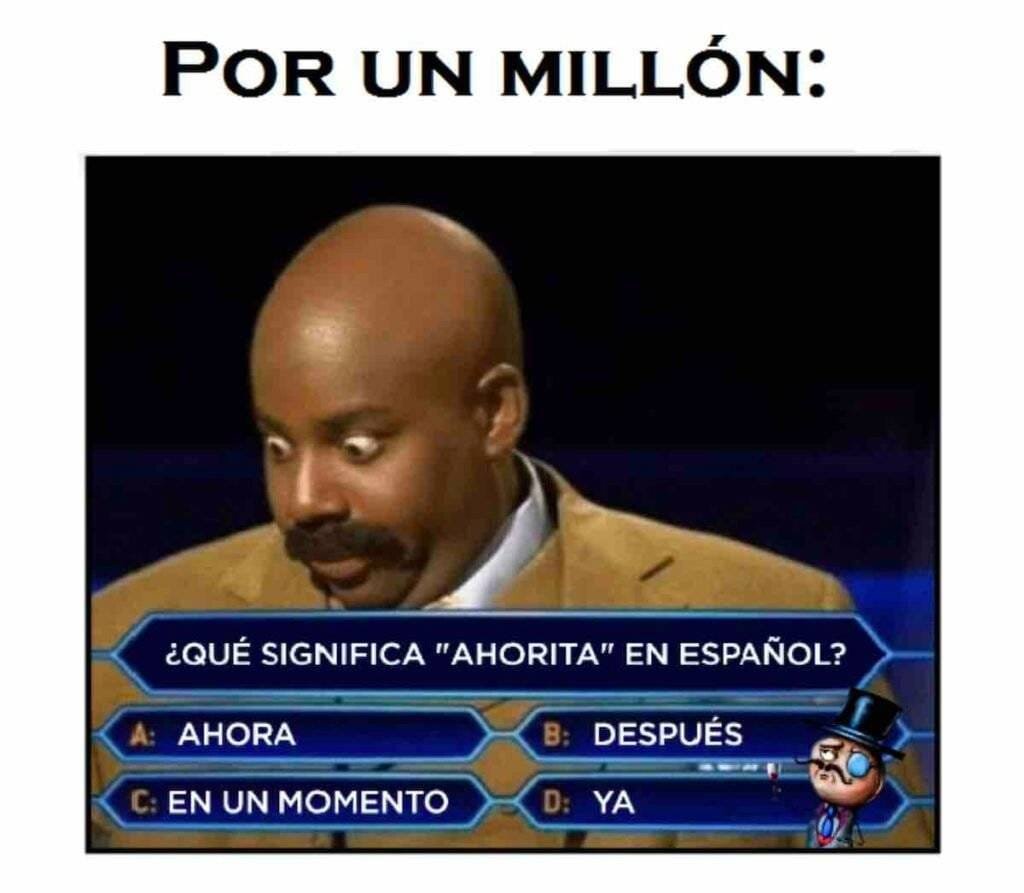

3. Filler Words and Frequency of Use of “Caballero” (guys)

One of the most notable features of the video is the repeated use of the word “caballero,” which can be loosely translated as “guys” or “everyone.” to address a group of people. This word, which in its basic form means “gentleman” or “sir,” is used in Cuban Spanish as a “filler word” (a word or phrase that someone repeats out of habit) to capture the listener’s attention or emphasize an idea. The speaker repeats it several times throughout the video to add weight to what she is saying, such as in: “Caballero, ustedes vieron…” or “Caballero, ya son las 10 de la noche…”

Filler words are common in any language, and in the case of Cuban Spanish, “caballero” functions as a catch-all word that doesn’t always carry its literal meaning, but rather acts as an interjection to add dynamism to the conversation.

In the video, “caballero” is used as an interjection, a way to address the audience, or to express surprise or exasperation. When the speaker says, “Caballero, ustedes vieron un pancito nada más” she is involving her listeners in an informal complaint about the small amount of bread she’s managed to get. The repeated use of “caballero” creates a sense of closeness and familiarity with the audience, reinforcing the collective and communal nature of Cuban culture.

4. Cultural Context and Expressions from the Video

Scarcity

The content of the video, despite having a humorous tone, accurately portrays the daily difficulties in Cuba without addressing political issues. Through small anecdotes, the everyday obstacles that are part of life on the island are presented, such as the scarcity of food, the reuse of products, and the creativity to face these difficulties. For example, the protagonist mentions that she reuses the coffee from the previous day, sweetening it with honey due to the lack of sugar, reflecting the adaptability of Cubans.

Additionally, there is a reference to the practice of reusing coffee grounds, that is, the solid residue left after preparing coffee. In many Cuban households, the grounds are reused, either as fertilizer or to make infusions. These types of practices demonstrate how, in a context of scarcity, available resources are maximized, a sign of ingenuity in the face of crisis.

The quality of bread is also mentioned, which is often poor due to a lack of ingredients, resulting in hard bread that takes on a sour taste. Such problems with food are just one of many manifestations of how scarcity impacts daily life.

Lines

Lines are a fundamental aspect of life in Cuba and symbolize both resilience and the economic difficulties of the country. It is common for people to form long lines to buy food or basic products due to scarcity and inefficiency in distribution. Often, people must queue very early, even before dawn, to secure a spot and obtain products before they run out.

This phenomenon has generated an interesting social dynamic. In lines, people converse, exchange information about where to find products, and create an informal system where everyone knows who is before or after them. There are phrases that have become part of everyday language, such as “Who is the last?”—an expression used when someone arrives at the line and positions themselves—or “To ask and give the last.” Asking for the last is used to join the line, and the person who indicates who is last “gives the last.” There’s also the expression “to cut in line,” which means bypassing others.

Although lines are a frustrating reality, they also show the ability of Cubans to adapt and socialize while waiting, transforming an unpleasant experience into a chance for social interaction.

Family and the Role of Grandparents

The video highlights the importance of family in the Cuban social structure. The grandmother, who wakes up early to get the bread, and the mother who prepares the coffee, show how daily responsibilities are often shared among different generations of the family.

The Cuban family serves as a support system of solidarity that transcends the immediate nucleus, involving all its members in a strong sense of community. Grandparents play an essential role not only as caregivers but also as guardians of Cuban traditions and family memory. On the island, daily tasks are distributed among all members, fostering an environment of mutual support, which is essential for facing economic difficulties. This network of family solidarity is a key pillar within Cuban culture, where unity and collective effort ensure the family’s well-being in times of scarcity.

Typical Cuban Food and Daily Moments

In Cuba, the traditional meal structure includes breakfast, lunch, and dinner, while snacks are often omitted due to economic constraints. The last meal of the day, instead of dinner, is often referred to as “comida.” In the video, several expressions are mentioned that reflect how scarcity has altered these eating habits.

For example, the phrase “to skip the snack” is common and refers to the omission of this meal due to a lack of food. Reheating leftovers from the previous day is also common, as there is a desire to avoid waste. Additionally, the expression “until further notice” is humorously used to indicate that the snack has been indefinitely suspended, referencing government announcements that often employ this phrase to communicate restrictions.

Another expression used is “to change the meal schedule.” In this context, “to change” means “to shift,” and what is suggested in the video is how scarcity affects families’ daily routines, forcing them to modify their habits and reflecting the flexibility people must have in the face of resource shortages. Another way to say “to change the schedule” would be “to postpone.”

We find the verb “tocar (to get)” in phrases like “what we got was white rice”. Here, the verb “tocar (to get)” is used to express what has been designated to eat that day, and it is a very common usage in everyday speech. This reflects the idea that you cannot choose what you eat, and it is evidence of how language has evolved to adapt to this new reality. The food is not chosen; “you get it” implying a lack of control over food options.

Regarding the expression “I have that on my big toe or in my heel”, it is used when something is very little. In Cuba, it is said that something goes down to one’s big toe to illustrate that it is insufficient, going down to the lowest part of the body to indicate scarcity.

Each of these themes highlights how scarcity not only impacts food but also daily life and Cuban culture. The use of expressions like “until further notice” or “you get the food” is an example of how Cubans use intertextuality in everyday situations. Each of these expressions carries a context that, if not understood, may lose a significant part of its meaning.

What is Eaten? – Cuban typical food

Currently, much of the typical food of Cuba and the best Cuban culinary traditions have been lost due to the economic situation in the country. The Cuban breakfast has generally been reduced to consuming bread, which, as shown in the video, is often heated in a pan and eaten without accompaniment, as any addition like cheese or cold cuts is considered a luxury accessible to few.

Coffee is another central element in daily Cuban life, although it is rarely consumed in its pure form. The mixture of coffee with peas is a practice instituted by the government, and over time, many people have become so accustomed to this taste that they even prefer to continue consuming coffee mixed with peas, even when they can afford pure coffee.

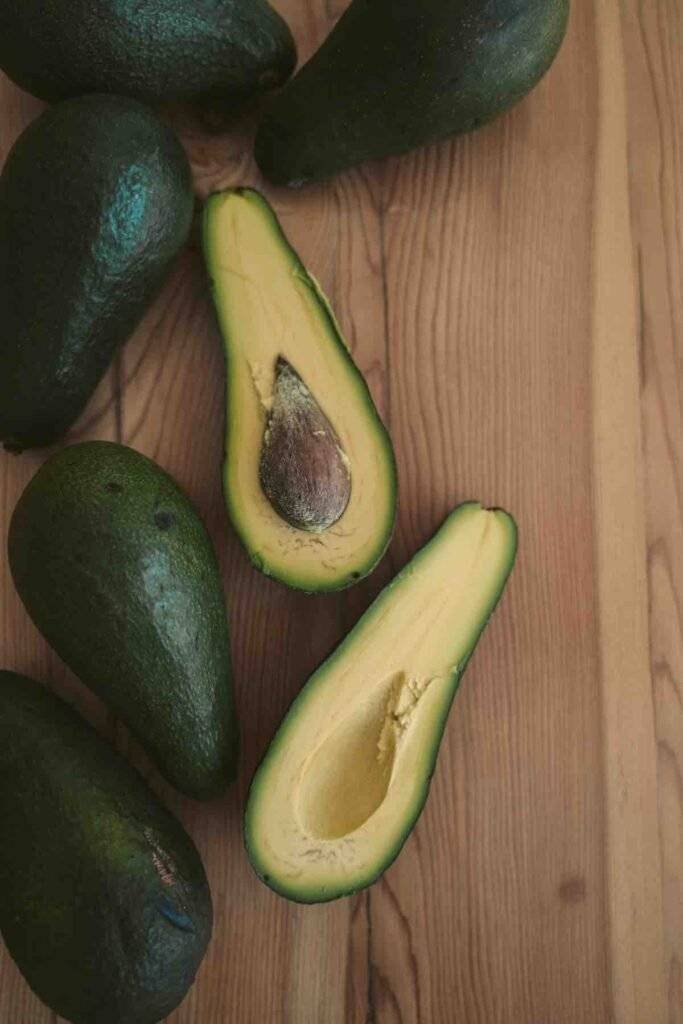

On the other hand, rice is absolutely essential on the Cuban table. In particular, the variety of congrí is a cornerstone of typical Cuban food and one of the strongest Cuban culinary traditions. For a Cuban, a dish without rice is practically inconceivable. Meals often lack animal protein, as it is considered a luxury that is not accessible every day, reflecting the economic difficulties of the island.

To delve deeper into how Cuban culture has been shaped by the country’s economic history and its implications in the kitchen, I recommend researching the evolution of food in Cuba and the influence of scarcity on culinary customs. An excellent resource for further exploration is the article The Cuban Kitchen by Raquel Rabade Roque, which provides a detailed analysis of Cuban cuisine over the years. I also suggest exploring studies on how economic restrictions have impacted eating habits at different times.

Finally, the pea is a food that came to Cuba through the culture of Eastern European countries, as it was uncommon on the island before 1959. Although initially considered a very humble dish, over time, it has gained an important place in the Cuban diet, being appreciated by many generations. In fact, many Cuban emigrants remember it nostalgically and even seek it out because it evokes memories of their past on the island.

This change in perception and consumption of the pea reflects how the Cuban diet has evolved, and today, the pea has become part of Cuban traditions, especially for the generation that grew up in Cuba from the 1960s onward. Thus, consuming peas is not only a necessity imposed by scarcity but also a symbol of resistance and adaptation within Cuban culture. This article elaborates further on this Cuban love for peas.

“The Law of the Branch”

The “law of the branch” is a unique expression in Cuban culture that refers to the custom of considering the fruits of a plant as the property of the person who has a branch growing within their land, even if the tree is planted on a neighbor’s property. This informal agreement grants the neighbor the right to harvest the fruits from that branch, reflecting a strong tradition of solidarity and collaboration among Cubans, who often share resources as part of their daily lives.

This practice highlights not only the creativity of Cubans in interpreting property rights but also how they adapt to local community dynamics. By sharing the fruits of a tree that may be on someone else’s property, the sense of community and coexistence is reinforced, making this tradition an important part of Cuban customs.

From a formal perspective, the “law of the branch” might seem unusual or uncommon in legal terms, but within the context of Cuban life, it makes perfect sense. This practice showcases the flexibility and adaptability with which Cubans face resource limitations, utilizing informal agreements that prioritize collective well-being over strictly legal norms.

“Making a Little Money”

In Cuba, the phrase “making a little money” is very common and refers to the need to generate additional income through informal or complementary activities. This type of expression reflects an economic reality in which official salaries do not cover basic needs, forcing many people to seek secondary jobs or parallel activities to supplement their income. Some additional activities are informally known as “the search,” a term that describes the opportunities or informal benefits a worker can obtain in their employment, usually through unofficial means.

“The search” refers to what a worker can obtain beyond their salary, whether through the appropriation of work resources or benefits derived from their work connections. The expression “to earn a little money,” often used in diminutive form, conveys the idea that this income is modest and supplementary, yet indispensable for survival. Many times, these activities can include anything from additional jobs to the use of work materials or resources for personal benefit, which, although informal, has become normalized in the Cuban economic context due to scarcity and necessity.

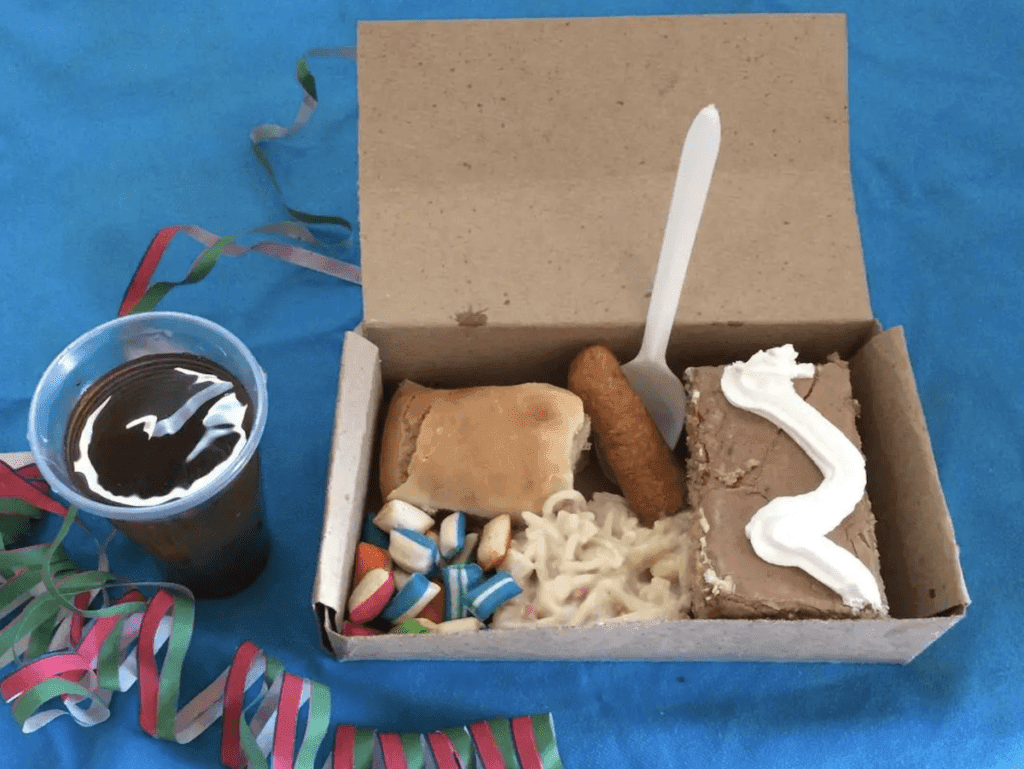

Little Bread Rolls and Birthdays

Birthday celebrations in Cuba, especially between the 1960s and 1990s, feature very particular Cuban traditions that remain in the memories of those who lived through that era.

Among the most characteristic elements of these parties were the little bread rolls, small and round, which were essential for any celebration. These rolls, filled with various combinations like ham or pâté, became a symbol of Cuban children’s parties.

Another distinctive aspect was the salad, which, almost always by accident, ended up alongside the cake. This resulted in a mixture of salty and sweet flavors that, while it may seem unusual, was quite common at birthday parties. This combination of flavors, although peculiar, is part of the typical memories of Cuban celebrations, being a deeply rooted characteristic of our identity.

As part of the Cuban birthday party traditions, cardboard boxes were used for the guests, which initially included a small punched spoon on the lid, which could be detached for use while eating. Over time, this spoon was no longer included, as it became more economical and practical to produce the boxes without it.

These boxes were an essential detail at the parties, made from recycled materials that gave them a unique touch.Years later, these birthday boxes began to be used in Cuba not only for parties but also to sell food, becoming a versatile element in Cuban culinary culture.

In summary, these elements—the little bread rolls, the combination of salad and cake, and the cardboard boxes—are part of a rich tradition of birthday celebrations in Cuba, which endures in the memories of those who grew up in that era. The following article provides more information about birthday boxes in Cuba.

Roofs in Cuba

In Cuba, the types of roofs vary according to construction style and geographic location, also reflecting economic and social differences. One of the most common roofs is the slab roof, constructed with cement and steel (rebar, as it is known locally). This type of roof is associated with higher quality and durability. When a person with this type of roof talks about it, they often say “on my slab,” as seen in the video.

Another type is the beam and slab roof, which, although widely used in older constructions, is more vulnerable, especially in areas exposed to salt, such as coastal regions. Over time, the oxidation of the steel and the wear of the material increase the risk of collapse for these roofs.

An improved version of this style is the beam and block roof, which offers greater stability than the beam and slab roof, but is still susceptible to corrosion from salt due to the metallic components of the beams.

In rural areas, it is common to find thatched roofs made from palm leaves. These roofs, in addition to being cool and economical, represent the indigenous architecture of the Caribbean. While they are valued in other places for their folkloric aspect, in Cuba they are generally associated with low-income housing.

Another common type following hurricanes is zinc or fiber cement roofs, provided by the government as a temporary solution. However, they are known for being extremely hot, affecting the comfort of homes.

Finally, there are tile roofs, especially French tiles, traditional in some older constructions. However, due to the lack of availability of these tiles today, their preservation has become a challenge.

This range of roof styles reflects both the architectural evolution of the island and the climatic and economic conditions faced by its inhabitants.

Power Outages

Power outages in Cuba are a recurring phenomenon that has become part of daily life, affecting multiple aspects of the daily routine and generating both inconvenience and frustration. The expression “the light went out” is commonly used by Cubans to describe these power cuts, which can happen at any time of the day, affecting everything from food preparation to work and study.

These outages, mostly planned by the government due to fuel shortages and ongoing issues with the electrical infrastructure, force people to adjust their schedules and seek creative ways to continue with their activities. However, despite these difficulties, Cubans have shown remarkable adaptability, developing ingenious solutions to cope with the interruptions and maintain a sense of normalcy amid adversity. These experiences reflect not only the resilience of the Cuban people but also their capacity to face challenges with ingenuity and solidarity.

Although the lack of energy resources is the main cause, the way the average Cuban faces these situations reflects their resilience. They have developed strategies to continue their daily lives despite the difficulties, transforming power outages into a part of their everyday reality, highlighting their ingenuity and creativity in the face of adversity.

5. Grammar and Structure

Madrugar (to Get up Very Early)

The verb “madrugar” is a regular verb that describes the action of getting up very early in the morning. Grammatically, this verb follows the conjugation rules of -ar verbs (madrugo, madrugas, madruga, etc.). It is interesting from a grammatical point of view because many languages do not have a direct equivalent verb to describe this action. The use of madrugar implies a cultural connotation of effort and discipline and is often associated with people who work or have early obligations.

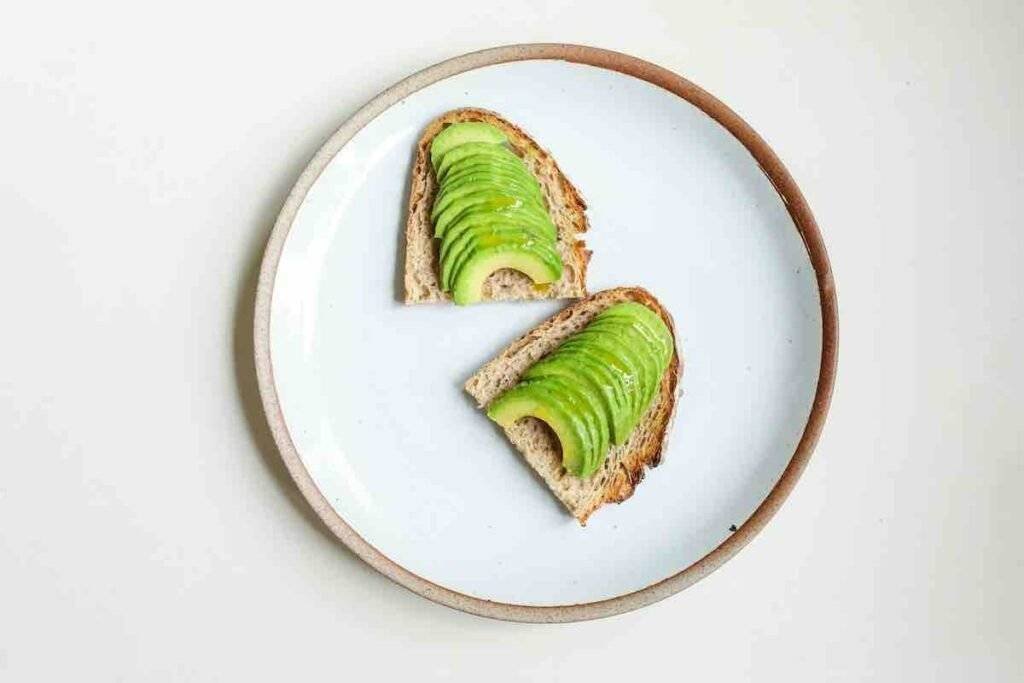

Lasca de aguacate (Thin Slice)

In Cuba, the term “lasca” is commonly used to refer to thin slices of certain foods, such as in the case of ham, where one speaks of lascas de jamón However, its use to describe portions of avocado is not as frequent or accepted in standard Spanish, where other words are preferred depending on the type of cut. Below, I explain the most common options:

Rodaja (slice): This term refers to thin, circular cuts, like those made with certain vegetables or fruits. It is suitable for describing avocado cuts made along the fruit when the result is thin. Example: “I cut the avocado into thin slices (rodajas) for the salad.”

Tajada (thick slice) : When the pieces are larger or elongated, the word tajada is preferred. It is ideal for describing thicker cuts of avocado. Example: “I served a thick slice (tajada) of avocado with the rice.”

Trozos (pieces): This term is more generic and is used for portions of any size or shape, without specifying whether they are thin or thick. It can be used in any context and is quite flexible. Example: “I added pieces (trozos) of avocado to the dish.”

In summary, lasca is common in some places for certain foods like ham, but it is not the most appropriate term for describing portions of avocado in standard Spanish. Depending on the type of cut, it would be better to opt for rodaja, tajada, or trozo to maintain clarity and precision when describing how the avocado is cut.

Colar y colarse (Strain and Cut In)

Both uses of “colar“ come from the same verb, but one refers to a physical act related to filtering, while the other is a pronominal verb (colarse) that acquires a figurative sense of social action. The difference between “colar“ and “colarse“ is an interesting example of how the same verb can have completely different meanings in diverse contexts.

In the video, the person uses the incorrect form “quien se cole“ when they should say “quien se cuele.“ The verb colarse is irregular, and in this case, it should be conjugated in the present subjunctive as “cuela“ for third persons. The correct phrase would be: “of whom se cuele.” This mistake is common when conjugating irregular verbs.

6. Speed and Rhythm of Speech

The video is distinguished by the rapidity of speech, a common characteristic in Cuban Spanish. Words blend together and are pronounced quickly, presenting a significant challenge for advanced students who need to train their ears to understand the continuous flow of words. This accelerated rhythm is a typical feature of spoken Spanish in Cuba.

In the case of the speaker, she exhibits a typical accent from the western part of Cuba, where phonetic phenomena such as the aspiration of the /r/ and the weakening of the palatal /y/ and /ll/ intervocalic can be observed. These traits mark an important difference in pronunciation and make Cuban speech particularly distinctive.

A crucial aspect highlighted in the video is the speed of speech. The speaker maintains a fluid and rapid rhythm, which can be complicated for advanced students since sound reductions and word unions occur, making comprehension more difficult. For example, terms like “chirriquitico” or “recuelo” are heard almost as a single sequence, requiring a more refined listening skill.

Spanish is the second fastest language in terms of speech rate, only surpassed by Japanese. This implies that students aiming to master Cuban Spanish, known for its accelerated rhythm, must actively practice with this type of discourse to improve their comprehension and achieve a higher level of fluency. According to an article published on Babel.com, a study by the University of Lyon in 2011, which analyzed seven languages, ranked the speed of speech in the following order: Japanese (7.84 syllables per second), Spanish (7.82), French (7.18), Italian (6.99), English (6.19), German (5.97), and Mandarin (5.18).

7. Conclusion

This video not only offers an intimate glimpse into daily life in Cuba but also serves as a valuable study tool for advanced Spanish students, especially those interested in Cuban Spanish. By analyzing aspects such as the accelerated rhythm of speech, the use of local expressions linked to Cuban traditions, and the phonetic phenomena specific to the region, students can deepen their listening comprehension and improve their communicative competence in authentic situations while exploring the rich Cuban culture.

Additionally, the transcription and detailed analysis allow students to delve into the interrelation between language and Cuban culture, helping them understand how social dynamics and circumstances of daily life, such as scarcity or the blackouts reflected in expressions like “se fue la luz,” influence language use. This exercise fosters greater fluency and connects learners with the essence of Cuban traditions, especially those related to typical Cuban food, reflected in its colloquial speech and unique expressions.

As we progress in future analyses of Cuban videos, I invite you to continue exploring this fascinating topic through more authentic videos or even by transcribing the content of similar videos yourself. This practice will allow you to further refine your listening comprehension and familiarize yourself with the nuances of Cuban Spanish. Don’t hesitate to apply these tools in your own learning!

This approach goes beyond grammatical structures to include the cultural dimension of Cuban Spanish, which is deeply intertwined with Cuban culture and its traditions, from the day-to-day marked by scarcity to the enjoyment of its typical food.

I invite you to share your own experiences with the Cuban language and culture in the comments. Have you heard any of these expressions in other contexts? What other words or phrases would you like us to analyze in future videos? Your participation enriches this learning community!

2 thoughts on “Cuban Typical Food: 7 Key Points to Analyze the Video”